Sewer Commissioners discuss possible plans for Cape Cod Canal outflow pipe

For years, Wareham officials have discussed building an outfall pipe that would discharge treated wastewater in the Cape Cod Canal.

A new outfall pipe would allow the department to expand its capacity to treat wastewater, which is currently limited by the size of the water purification plant and the location of its outfall pipe in the Agawam River.

Because the Agawam River is ecologically sensitive, the amount of even well-treated wastewater that can be discharged there is very limited. By moving the outfall pipe to the Cape Cod Canal, the plant could discharge up to 3.5 million gallons of water each day. Currently, the plant processes 1.56 million gallons a day, and it is nearing capacity.

The Sewer Commissioners put a moratorium on new sewer hook-ups until at least July, but it’s likely the plant will continue to struggle with capacity as the town has committed to process more wastewater than is physically possible at the current plant.

In October, the commissioners hired the Kleinfelder engineering company to map out possible routes for an outfall pipe to the Cape Cod Canal. The pipe would merge with the existing outfall pipe at Mass Maritime Academy in Buzzards Bay.

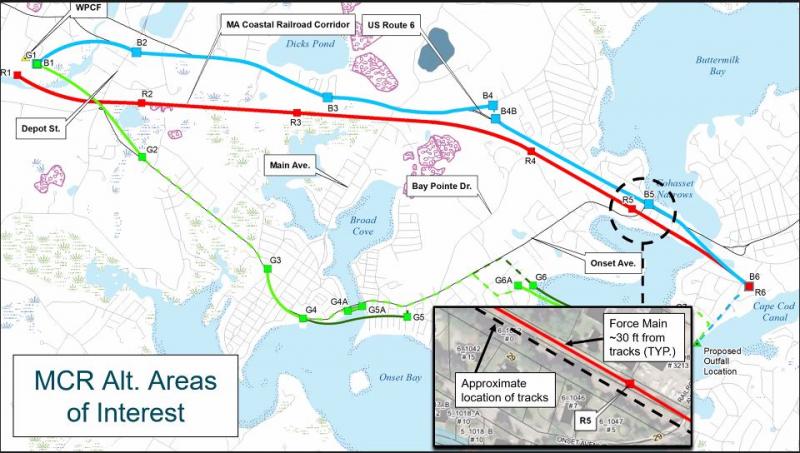

The engineers came up with three possible routes for the pipe, which would start at the town’s wastewater treatment plant off Tony’s Lane, near the intersection of Cranberry Highway and Sandwich Road.

The three routes pitched by the engineers followed Onset Avenue, the train tracks and Cranberry Highway.

The engineers said that the train track route would likely be the best option.

That’s in part because the structure of the train tracks with wide buffers on each side would minimize the number of necessary easements, and in part because those buffers would give workers ample room to assemble long sections of pipe.

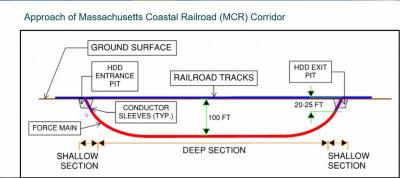

The pipes would run 100 feet below ground and only come closer to the surface about four or five times along the train track route.

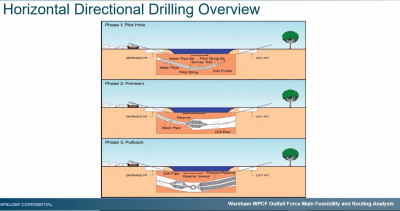

The pipes would be installed through a process called horizontal directional drilling, which allows crews to bore holes deep underground for long distances. After drilling the hole, crews work quickly to insert a pipe.

Closer to the surface, especially in areas with sandy soil, Kleinfelder engineer Dennis Doherty said that crews would use steel “conductor sleeves” to reinforce the pipes and prevent settling.

Doherty said that the main concern expressed by railroad officials was that the pipes could settle, leading the train tracks to misalign. Railroad tracks can safely settle up to .5 inch, and Doherty said that at most, the pipes would cause up to a tenth of an inch of settlement.

Also, the pipes would run about 30 to 50 feet away from the train tracks.

The engineers also proposed two other routes, one that would run alongside Onset Avenue and one that would run alongside Cranberry Highway.

Both those routes would require much more complicated installation. For a section of the pipe along Cranberry Highway, Doherty said, crews would likely have to assemble the pipe in the parking lot of Water Wizz — precious open space in the area — and drag it along the road before installing it.

Onset Avenue features a number of large glacial rocks that would complicate the planning and could cause problems if a drill hit one unintentionally.

The Sewer Commissioners were enthusiastic about the idea, and said they and Kleinfelder should reach out to the MBTA (Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority) as soon as possible to see if the organization, which owns the tracks, seemed likely to grant permission for the project.

The total estimated cost of the project was not made public, but a Kleinfelder representative said the firm has staff who specialize in helping municipalities obtain grants for these types of projects. Additionally, officials have discussed sharing the use of the pipe — and the costs — with surrounding towns.