Artificial intelligence comes to Middle School math class

When it comes to technology, Wareham Middle School seventh grade math teacher Jen Crimaldi admits that she’s “old school.”

However, she’ll “try anything once,” and wants to prepare her students for what the future will bring.

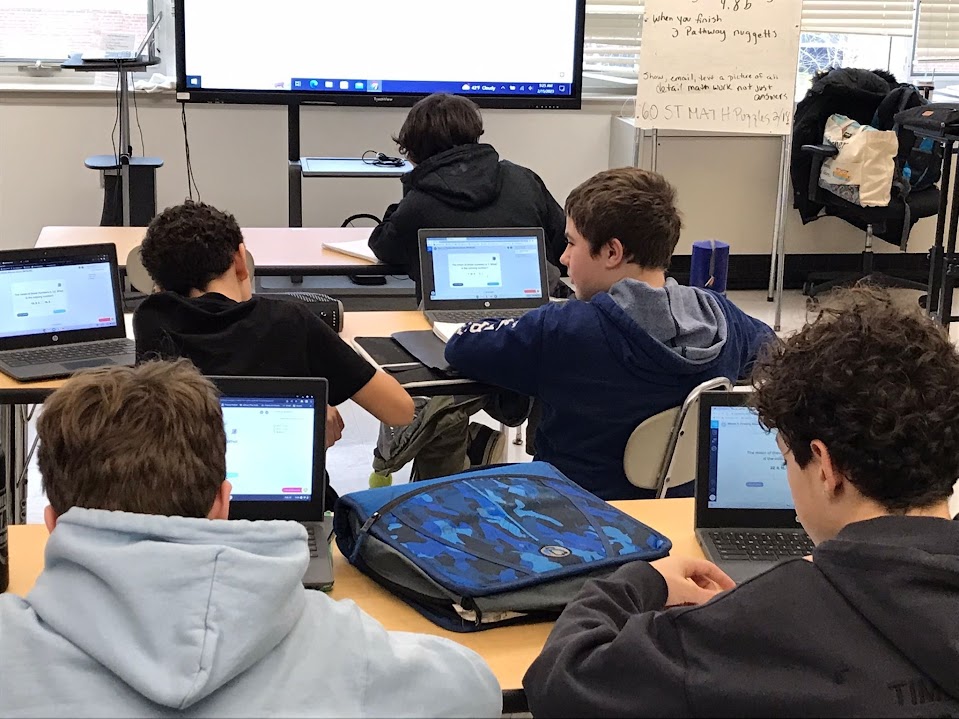

This January, Crimaldi’s students began using programs developed by Century, a British artificial intelligence company, as part of their learning. Wareham is the first school district in the United States to use Century.

Century’s AI, like all AI, is trained to sift through massive amounts of data, observing and learning in the same way that a human being would.

Century can analyze hundreds of test results to pinpoint what math concepts students are struggling with. Crimaldi creates assignments and homework based on Century’s findings, while Century gives the students personalized lessons, called “nuggets.” These nuggets can be videos or slideshows, depending on how the student learns best.

Crimaldi said that it took her students a while to get used to Century, but they’re doing “fairly well.”

“I haven’t heard any complaints,” she said. “I have really raised the bar for students this year, and I would say that 80% of them meet that bar.”

According to data from Wareham Public Schools, 157 students have completed 3,308 nuggets so far. They have answered a total of 23,519 questions with 79% accuracy.

Assistant Superintendent Dr. Andrea Schwamb likens the arrival of AI to when computers and the internet were first introduced in schools. While others were skeptical, she saw an opportunity.

Schwamb thinks AI can identify students’ needs much faster than a human teacher can.

“Say you have kids from grade two up to grade eight,” Schwamb said. “Tell me realistically how a teacher is supposed to do that for all those kids, 100 of them a day if you have five periods. It’s absurd to ask teachers to do that.”

Schwamb praised Century’s “personalized” learning program, designed to work with every student at their unique level.

“When I have a seventh grader coming up to me who has a fifth grade math level, I can’t possibly catch up to them,” Crimaldi said. “That’s a big struggle for me.”

“But you also have a class to teach,” Schwamb said. “How are you supposed to do all of that in 50 minutes? But that’s what everyone on the outside expects us to do.”

Schwamb was emphatic that an AI never can and never will replace human teachers.

“There’s nothing better than the relationship between a teacher and students,” she said. “It’s the most important thing by far.”

If anything, Schwamb said, students using AI receive more support from the teacher, who helps them navigate the new technology.

Schwamb first became interested in AI when she saw Watson, IBM’s question-answering computer, beat “Jeopardy” champions Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter.

Since Watson is no longer being used in education, she had to find another AI to use in Wareham Public Schools.

“This particular company seemed a little bit more innovative,” she said of Century, “and had more access to different kinds of content.”

She especially liked how Century’s programming wasn’t “canned;” the school could customize it to suit its own needs.

Wareham Public Schools had been in touch with Century since before the pandemic, but the ensuing remote learning blitz made Century too busy to be reached.

Schwamb and several school officials, including Director of Technology Bonnie Lasorsa, met with Century in April 2021.

“They felt that they had perfected seventh grade math, specifically,” Schamb said, “and asked if we had teachers willing to pilot the program.”

At the time, Lasorsa was chair of the school math department and a sixth and seventh grade math teacher.

“In my own classes, I’ve tried a lot of things,” she said. “If I have a student that doesn’t understand, say, dividing fractions, I know that they’re struggling with it, but I don’t always know what the issue is.”

Lasorsa said that AI lets teachers like her know aspects of a student’s learning background that they would otherwise have no knowledge of. This lets them know where to focus their efforts.

“You can spend more time with kids,” she said, “and that’s actually the best part of technology.”

Special education teachers are also currently working with Century. It is just as much of a learning experience for them as it is for the students.

“Change in education is like moving an ocean liner,” Schwamb said. “It will be slow and deliberate and intentional, and it will be driven by teachers and what they need.”

Schwamb won’t know the impact AI has had on learning until she sees the MCAS scores this August. For now, she is interested in expanding AI to other subjects and grade levels, although “the challenges of AI are clear.”

Take, for example, ChatGPT, a “chatbot” program that uses artificial intelligence to answer questions and generate written content.

To many school officials, it’s a threat — a potential gold mine for cheating. On the other hand, Schwamb says, it can help students gather information and improve their writing.

Lasorsa is “intrigued” by ChatGPT’s ability to take a collection of random tidbits and synthesize them into a coherent text. She wants to create a conversation about how students can use such technology to their benefit.

“I think it’s something we need to look at,” she said, “but we need to look at it thoughtfully and with some training for teachers.”

Schwamb is “on the fence” as to whether chatbots will have a place in the classroom. The ChatGPT website is currently blocked for Middle and High School students, and for the record, Schwamb thinks she can write better than it can.

“[As] we’re going to start to embrace more artificial intelligence,” she said, “we’ll also have to think about ethics and morals and integrity and all of those other elements that come with developing human beings.”