Restoring cranberry bogs could cut down on nitrogen pollution

The Buzzards Bay Coalition recently released a report bringing together 10 years of research into the impact of cranberry bogs on water quality.

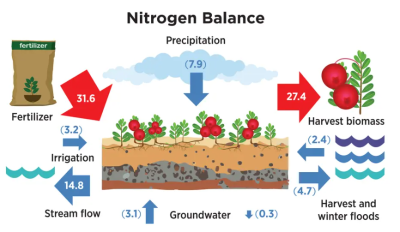

Cranberry farming accounts for approximately 20% of the nitrogen released into the Wareham River, according to the report. Retiring the worst-polluting bogs and restoring them to wetlands — a trend that is already starting for economic reasons — could cut that pollution almost in half.

The information collected through the Coalition's research helps inform efforts to reduce nitrogen pollution in Buzzards Bay, including the Wareham River watershed.

The state recently released a draft Total Maximum Daily Load limit for how much nitrogen can safely be released to Wareham's waters.

"In order to have a good TMDL, you have to know how much nitrogen is coming from the different sources," said Rachel Jakuba, vice president of Bay Science with the Coalition.

Jakuba added, "There has been debate in the past about whether we knew well enough how much nitrogen is coming from cranberry bogs. The science that we did gives me assurance that we do know how much nitrogen is coming into these waterways from cranberry bogs."

The Coalition found in its research that not all bogs contribute equally to nitrogen pollution.

Some types of bogs, called "flow through bogs," are located directly next to streams, and have free-flowing water running directly through them. These bogs emit the highest amount of nitrogen, as the nitrogen used in fertilizer gets washed into the ecosystem.

The Coalition's report says if all the flow-through bogs in the Wareham River watershed are retired and restored to wetlands, it would reduce the amount of nitrogen produced by cranberry bogs by 40%, leading to a 10% decrease in the overall levels of nitrogen pollution in the watershed.

Retiring the cranberry bogs directly reduces the amount of nitrogen in the environment because farmers will no longer use fertilizer in that location. Restoring them to wetlands has a more indirect impact. The vegetation in a wetland can absorb nitrogen from the water that flows through it, so helping to reduce the impact of upstream nitrogen sources.

The effort to retire and restore cranberry bogs can also be an economic benefit to the farmers involved.

The cranberry industry is developing new cultivars of cranberries that are more profitable to grow, said Jakuba.

She added, "A lot of what has happened, as new bogs are being built in other parts of the country, is they're putting in these new vines that produce more berries per unit area."

That makes older bogs — like many of the flow-through bogs highlighted by the Coalition's report — less profitable.

The Massachusetts Department of Ecological Restoration has grants available to restore cranberry bogs to wetlands, said Jakuba. These could helping local growers turn their less-productive bogs to wetlands, while focusing their resources on more-productive strains of cranberries.

(2).jpg)